Growing up in Mississippi in the mid-20th century, I believed we white folks had it all figured out. We knew who we were: good, humble, God-fearing people, proud of our heritage and state. Sure, we didn’t travel much, but we read the papers, flipped through magazines, watched plenty of movies, and devoured TV. The stories we consumed never challenged us—they affirmed our beliefs. No one asked us to feel guilty about slavery, the Civil War, Jim Crow, or what was happening right under our noses. White folks everywhere, North and South, seemed to have this quiet agreement: certain things just didn’t need talking about.

But then the ’50s and ’60s hit, and suddenly, that easy agreement started to fray. The national news began showing Mississippi in a whole new light, and it wasn’t flattering. We learned that being called a “racist” was something we should feel ashamed about. It hadn’t stung like that before. Heck, being called a “Yankee” or someone who liked Black people? Now, that was an insult. But “racist”? That felt like being told you had feet—just a fact. But as the Civil Rights movement gained steam, the word started sticking. Racism took on a Southern twang and a Mississippi fingerprint, like we invented it.

The more the movement grew, the more Mississippi seemed to be the center of every ugly headline: church burnings, police beatings, Klan murders. It was a harsh spotlight for a state that liked to think of itself as polite and welcoming. We were used to being defined by the Spanish moss and grand old houses, by smiling Black people singing spirituals. But now? Now, we were the villains—burning crosses, wearing white robes, and killing civil rights workers. Yes, those things happened, but most of us told ourselves that wasn’t who we were. We blamed a handful of hotheads—people we liked to think of as distant cousins we couldn’t control. As the rest of the country pointed fingers at Mississippi, we pointed at someone else.

Once a comfort, TV became a place where our identity was under siege. The news might be against us, but our favorite shows still felt like a safe space. The Andy Griffith Show on Mondays, The Beverly Hillbillies on Wednesdays, and Gunsmoke on Saturdays—that was entertainment! But Sundays? Well, Sundays got complicated. The Ed Sullivan Show, once a favorite, started featuring more Black performers. Ed wanted us to respect them and admire their talent. That was a tough sell for a lot of folks here. We were okay with Black people on TV, as long as they were there to be laughed at, like Amos and Andy or Rochester from The Jack Benny Show or the ubiquitous Black maid on sitcoms. But take them seriously? That was pushing it. So, we adjusted our rabbit ear antennas, and tuned into one of the other two channels, hoping for something better.

Enter Bonanza. The show was a hit right out of the corral gate. Sunday nights became Bonanza nights, and we couldn’t get enough of the Cartwrights and their idyllic Ponderosa ranch. It was wholesome TV—a father and his three sons living in what seemed like heaven on earth, all in glorious color. If you knew someone with a color TV, like our neighbors, the Hefners, you made sure to drop by just in time for Bonanza. Those snow-capped mountains and majestic pine trees were mesmerizing. The show sold more color TVs than any ad campaign could dream of.

In Mississippi, no TV show captured our hearts like Bonanza until Hee-Haw came along later, but that’s a different story. Preachers even knew better than to let evening services run late on Sundays, or they’d find the pews empty before they finished the benediction. Everyone needed to be home by 7:55 to warm up their sets so they could hear that famous theme song. This was long before DVRs or streaming; miss an episode, and you were out of luck unless they reran it in the summer. Missing Bonanza meant missing out on being part of a shared moment with your neighbors, and nobody wanted that.

So, when the cast of Bonanza announced they were coming to the Jackson Coliseum, we were thrilled. Our beloved Cartwrights, right here in Mississippi! It’s all anyone could talk about. But then, everything fell apart. Just days before the event, Hoss Cartwright—the gentle giant everyone loved—dropped out. The reason? He found out the show would be segregated, and he wasn’t having it. The rest of the cast followed his lead.

Mississippi lost its mind. Let me put it in perspective: Medgar Evers, the renowned Civil Rights leader, had been assassinated the year before right in front of his Jackson home, and that barely ruffled a feather in some corners. But Hoss calling us out for being racist? That hit home. Hoss! Our Hoss! The sweet, good-natured character we considered practically family. We thought he understood us. But there he was, calling our way of life “repugnant.”

And then, insult to injury, they announced that Donna Douglas—Ellie Mae Clampett from The Beverly Hillbillies—was supposed to replace the Cartwrights but backed out for the same reason. Ellie Mae, the lovable, simple hillbilly, thought we were repugnant, too.

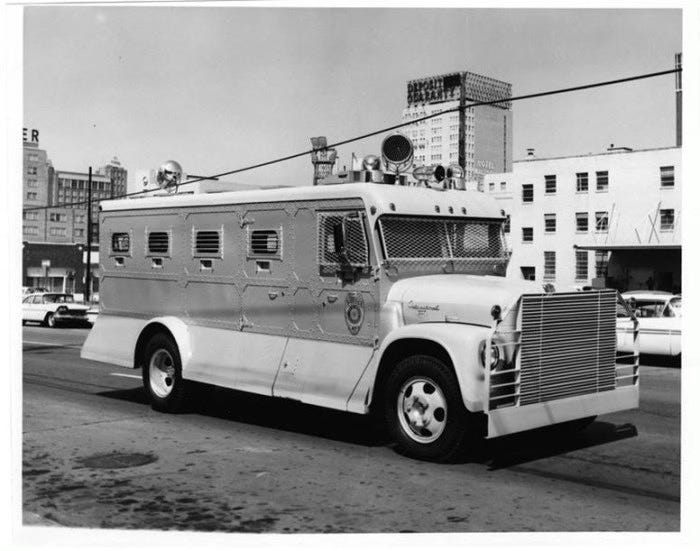

Jackson’s mayor, Allen Thompson, took it all pretty hard. He was already jumpy, worried about more Black protests like when Evers, his arch-nemesis, was gunned down. He had even gone so far as to buy a militarized vehicle for those envisioned riots—an International Harvester Loadstar 1600 outfitted with armor, bars, searchlights, sirens, and mounted machine guns. It was dubbed “Thompson’s Tank” after the mayor. You could tell he was itching to use it, perhaps eager to make a name for himself like George Wallace in neighboring Alabama. Wallace had already gained national attention the year before by proclaiming: “segregation today … segregation tomorrow . . . segregation forever.” There was talk of him running for president.

Thompson wasn’t going to let Hoss get away with it. He went on a campaign to boycott Bonanza, telling everyone to stop watching, stop buying products advertised during the show, and stop letting race-mixing TV into our homes. He was sure his protest would catch fire across the South like Wallace’s had. But it didn’t. People stopped talking about Bonanza out in the open but still watched it—sometimes with the shades pulled down. The show remained the top-rated program in Jackson, and Chevrolet sales didn’t suffer.

The outrage eventually died down. And for me, well, I was just a teenager at the time, but Hoss’s stand stuck with me. I started to think he might have a point. The blinders we’d all worn so comfortably were slipping if only a little.

As for Mayor Thompson? He did get to roll out his tank—though it didn’t go as planned. During a protest at Jackson State, a tear gas canister went off inside the tank, forcing the police to abandon ship while the students laughed.

Years later, in a fitting twist, the Jackson airport, once named for Thompson, was renamed in honor of Medgar Evers, the civil rights hero who had died under his watch.

But to the mayor’s credit, it wasn’t long before he softened his stance on integration and took on the powerful segregationist forces, a stance that did little for his political prospects.

Maybe, just maybe, Hoss got to him, too.