This piece marks another departure from the essays and memoirs I’ve shared with you. Periodically I will be posting chapters from a novel I set aside years ago and have recently begun rewriting. Chapter 1, if you remember, was entitled “Swap Dog Kin” and introduced the characters of Violet and Gran Gran. Chapter 2 introduces David Lee Brackett, a white boy of 11. From time to time, I hope to share additional chapters—though not necessarily in order. Still, I intend for each to stand on its own as a story worth your time.

Pa raised the piece of pine kindling over his head like he meant to split me in two. For a second, I froze, heart hammering, legs twitching to run. Then something inside me snapped, like reins breaking loose, and I bolted.

My bare feet slapped the floorboards. I tore across the front room and flung open the screen door. It screeched on its hinges; then I was gone, swallowed by the thick, steamy September night. My feet barely touched the porch steps before I hit the dirt yard and the rutted track that led to the big road, and then the four dark miles to Hardin's store and a phone. I'd never run that far before, and my legs tangled beneath me, clumsy with fear. I lurched forward, stumbling like a calf born too early.

Halfway down the track, I heard Pa's boots pounding behind me, each step louder than the last. I glanced back and caught the flash of his undershirt. He was close now, the stick still in his hand, his arm outstretched.

“Keep away from Hardin!” he yelled.

I'd never once outrun Pa. The pounding of his boots soon drove out the thin slap of my bare feet. I looked back again. He was reaching out for me and wielding the piece of split pine like a club.

The fear rose like bile, but I kept running. Just before he reached me, my feet betrayed me. I tripped and rolled down hard into the brush of a deep ditch. My head cracked against something solid. Light burst behind my eyes. I wasn't knocked out, but the world tipped sideways, and I knew if I moved, he’d see me.

So, I didn't.

Play dead. Ma's voice rose through the panic. Like a hognose snake.

I told my heart to hush and return to its cave inside my chest. I reined in my breath and pulled back on the panicked gulps until only a steady current of air flowed undisturbed to the bottommost regions of my belly. I imagined my lungs full, as light as circus balloons, lifting me into the protective dark of a moonless night.

This is what I was best at—locating the calm eye of danger and vanishing into it completely, like a marble slipping into a black velvet sack.

Blood trickled down my face, pooling in my eyes. But I didn't move—not even when I heard him pause above me and shout into the dark, “Keep away from Hardin, boy! You hear me?”

Then, slowly, the heavy boots turned back toward the house.

Maybe Ma got away.

When the silence held, I pushed to my knees and waited for the world to stop spinning. I didn't dare touch the wound, afraid of what I might find. Instead, I wiped my face with the tail of my shirt. The ground tilted when I stood, and I vomited into the ditch. The cicadas and frogs screamed at me to keep going. So I did, staggering off again into the dark Delta night.

Only an hour earlier, we'd been sitting down to supper. But my mind wasn't on eating. I couldn't stop looking at Pa and the Luger pistol beside his plate. His color had gone bad, gray and hollow, and his eyes were ink-black wells. That wildness burned inside him. I knew the signs. Whereas most children learned to tell time by clocks, calendars, the sun, or the moon's fullness, by age eleven, I kept time by where my father was in his unrelenting orbit, from light to darkness and back again. When he acted as he did tonight, I knew it was time to crawl deep into myself, not moving a muscle, and watch and listen with every nerve.

Ma moved soundlessly from the stove and, with deliberate calmness, set a stoneware bowl of rabbit dumplings on the oilcloth. It was Pa’s favorite, but he gave no sign of recognizing what Ma had placed before him. His panicky eyes, red from broken vessels, showed pupils as big and dark as inkwells. When he spooned the dumplings onto his plate, his hand noticeably shook with an electric shiver that seemed to ripple through his entire body.

Pa stopped chewing, and his expression went slack. There followed a look of bewilderment. He spat a mouthful of dumplings onto his plate and wiped his mouth on his sleeve. "This don't taste right."

"Maybe I scorched the gravy," Ma said evenly. "Want me to fix you something else?"

She tucked a strand of hair behind her ear. Calm as ever. But I saw her hand tremble.

She'd been sick too—coughing more, hiding bloody handkerchiefs. Her eyes were too big for her face. I feared she was dying.

That's when Pa dropped his spoon like it shocked his fingers.

"Rat poison!" he bellowed. "I can taste it!" His eyes locked on mine. "Don't swallow, boy! Spit it out!"

I nodded. Touched my throat like it burned. You never contradict Pa when he's like that.

"He told you to do it, didn't he?" he snarled at Ma.

"Who, Royall?"

"You know damn well who! He's been sneaking through the house! Watching me through the shadows."

Ma reached for him. "Royall, honey, nobody's trying to do you no harm," my mother said. She patted his hand. "Nobody in the house but me and David Lee."

But he wasn't listening. He clutched his throat, howling. Then he flipped the table. The pistol hit the floor and fired. A window shattered.

I dove between the pie safe and the stove. Ma kicked the gun under the oilcloth.

Pa gulped water straight from the pump. Trembling. Wild-eyed. Ma stepped toward him.

"You're here with your family that loves you," she said.

He grabbed her shoulders.

"Tell me his name, Beth Ann!"

She went limp. Just like the hognose snake.

"David Lee," she said, calm as breath. "Run. Hardin's store. Use his phone."

Pa spun toward me. "Don't bring that bastard into this!"

But he was already lifting the stick.

I looked into his face, trying to find the man who taught me to swim and run trotlines, who bounced me on his shoulders while he did a jig—but he wasn't there. It was not him I was betraying. I made myself move. One step. Then another.

Then I was gone.

Hardin’s store crouched low in the starless night. By the time I reached the porch, I was dripping with blood and sweat. I pounded on the screen door until a light flicked on inside.

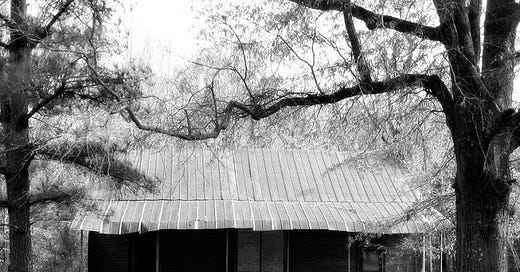

Only then did I wonder why the most notorious man in the county would even give me the time of day, much less use his phone? Pa had done jobs for George Hardin over the years, but they sure didn't seem to care much for one another. Just Hardin’s look was enough to scare most men into sniveling children. Massive as a live oak, Hardin dressed in a crisply ironed white broadcloth shirt and stiff wool vest spanned by a silver chain that disappeared into one pocket. And he was never without his pistol, which he kept stuck in the back of his belt. With his big gun, he shot people who got behind on their accounts or government men who tried to shut down his bootlegging. He buried his victims under the back-room floor to watch his hoarded treasure like pirates do. That's what the kids at school said, and I had no reason to doubt them. Some of my worst nightmares took place in that back room, which the man always kept locked. On those rare occasions when my mother sent me to the ill-stocked store, the man always gave me a flinty, impassive look, as if he were thinking of adding me to the collection of bodies buried under the floorboards.

Angry footsteps rattled the jars on the shelves. Then the door flew open.

"Who the hell—"

He looked furious at being disturbed. Then I saw the .38 pointed at my head.

"It's me—David Lee Brackett," I gasped. “My ma… she needs help…”

Hardin's scowl deepened when he saw my bloodied face.

"God damn! That son of a bitch."

My legs gave out, and I felt myself go down. Mr. George kicked the screen door open and caught me one-handed. He hoisted me into his arms and toted me to the back room like a tree log. He laid me down on a sack of corn.

"You gotta call the sheriff," I said.

He was already moving out the back door.

I gazed fretfully about the room, looking for grisly signs of murder and midnight burials. Through the shadows, I failed to see any dead bodies lying around. I saw a colorful picture of a naked lady wearing a Santa Claus cap nailed to the wall. She was letting folks know it was December 1933, which it wasn't. I knew it to be 1936, and it was September. I figured the man was more partial to the picture than the right date.

Several wooden crates labeled Old Kentucky Bourbon, which Pa hauled in from New Orleans on Mr. George’s trucks, were stacked off to the side, next to a battered desk. Shelves held fruit jars filled with what looked like water, but I suspected it was the cheaper moonshine my father kept around the house for when demons visited.

On the desktop sat a large box, wooden with brass fittings, old and scarred. I propped myself on my elbow to gain a better view. The box was open and sat amongst several tall stacks of bills. I never imagined that much money could wind up in the same place. It was Hardin's treasure chest! Maybe Mr. George was a pirate after all!

When I heard his footsteps, I dropped back onto the sack to avoid getting caught. The man had returned with a dishrag and a pan of water. He made a few quick dabs at the blood before handing the rag to me.

"Here," he said. "You know your face better than me. Mop it up some so I can tell what's your blood and what's your innards."

He walked over to the telephone on the wall, and I heard him ask for Doc Perkins.

"Ma…" I said, too spent for any more words.

"I'll get to it," he snapped at me.

While Mr. George waited on the phone, I noticed something else. In the wall below the lady was a dark hole where boards were missing. I hoped it wasn't what my suspicions told me it was. I glanced away to avoid being murdered and stuffed behind the wall for knowing secrets.

Mr. George finally had the doctor on the phone. "Brackett's having one of his crazy spells. Gave his boy a nasty gash."

"Pa didn't hurt me!" I cried. "Told you I fell!"

George gave me a skeptical look and continued. "Need you to come out to the store and see about him. Key to the front will be behind the Clabber Girl sign next to the door. Key to the back room, I'll leave it in the register. Don't let anybody in. I'm heading out to Brackett's house this minute to see about Beth Ann. Might need you there, too."

It unsettled me how the man had called my mother by her first name. It seemed weighted with a history unknown to me.

The second call he made was to the sheriff, who lived nearby. He told him to switch on his siren and pick up Pa.

"You'll get there faster than I can," he said. "And if you shoot him, it'll be legal."

"Don't hurt him!" I called out, pulling myself up again. Then I repeated what I had heard my mother say a hundred times, the thing that explained everything. "He don't mean it."

Hardin ignored my plea. "Listen, Colly. Keep him locked up till you can find Holt."

Holt was Pa’s best friend, if a colored man could be called that. He was also the best hunter in the county; he had a special way of breaking mules, wild dogs, and Pa when the devil was riding him. Holt would take him off to the woods and not bring him back until he had beaten the demons. I had seen the rope burns on my father’s wrists where Holt had bound him to keep him from hurting himself.

Hardin hung the phone in its cradle.

"Pa don't mean it," I said again. "It ain't his fault."

"I been knowing him longer than you have, boy," George said. "And I guarantee nothing is ever your daddy's fault."

From his vest pocket, he pulled out his polished silver watch and flipped open the cover. Under the hanging light, it reflected like the moon in his giant palm. It might be the most beautiful thing I have ever seen.

Mr. George glanced at me, and I felt he had caught me prying into something I shouldn’t. I quickly shifted my eyes as the man shut the lid with a sharp, decisive click.

"Colly Percy's nearby," Mr. George said, slipping the watch into its pocket. "He'll be out to see about Beth Ann in a couple of minutes."

Again, I reacted to the familiar and respectful way the man used my mother's name. It lacked the venom he had used when speaking of my father.

He walked over to me and knelt. "Let me get a look at that."

He reached out with a hand as big as a cypress knee and brushed my hair back from my forehead as gently as my mother would.

I held my breath under his studied gaze.

"Bleeding mostly stopped, but it'll take some stitches. Man needs him a scar."

"Yes, sir."

"Doc'll be here directly and get you fixed up while I go see to your ma. You be alright by yourself?"

"Yes, sir."

But he made no motion to leave. His hand remained resting on my forehead, warm and dry. He no longer studied the gash, but seemed to take in the entirety of my face now. His hard blue eyes had gone soft.

My own eyes filled. A whack to the head didn't draw a tear from me, yet what I saw in this man's face nearly destroyed me.

"Son," he said, "this room is yours anytime you want it. Nobody's going to hurt you here."

I nodded, unable to get the words past the catch in my throat.

Mr. George unclasped the watch from its chain and handed it to me. "Keep an eye on this till I get back. Don't want to lose it."

The watch was warm, and I clasped it tightly not to lose the heat from the man's hand.

George Hardin rose tree-tall again and turned toward his desk, once more revealing the gun in his belt.

"Don't hurt him," I said again.

Hardin didn't respond. He placed the money into the box and padlocked it. When he hefted it, a square of stiff paper spiraled from the desktop to the floor. It had been only a second, but the picture appeared to be of a much younger child. Mr. George bent over to scoop it up.

He walked the box towards the naked lady, but then stopped. He turned to me. "Don't look, boy. Shut your eyes."

I did as I was told, not asking why or daring to peek. After a while, I heard the door open. I kept my eyes closed, now too tired to open them.

I kept safeguarding the watch, gripping it tightly in my fist, determined not to flip back the silver lid to examine its numerated face lest it reveal something of the man he would rather remain hidden. George Hardin, I realized, was a man of many secrets. I needed to show him I’d always kept confidences.

The last thing I heard was the comforting click of the lock, followed by the man's heavy steps fading as he crossed the store.

I lay the watch against my chest, and my heartbeat sought to match the steady cadence of its metallic strokes. Relieved of the need to be careful of my father or shield my mother, I knew that, for now, I had a safe place of my own.

I wouldn't tell a soul about the treasure chest or the secret place behind the wall. Nor would I ever ask about the photograph that had fallen to the floor or if the child was someone the man loved. I would never let him know how, that for an instant, I longed to be that boy, protected from all things that could harm, whether they meant to or not.

Share this post