I first heard the term during treatment for alcohol addiction: geographical cure. The idea is simple—if you change your surroundings, your job, your relationships, maybe even your name, you can outrun the past. It’s meant as a caution: no matter how far you go, you take your past with you. Or as they say in AA, wherever you go, there you are.

But for me, flight has often been the thing that saved me. I’ve clung to more than a few geographical cures, each a desperate attempt at reinvention, a frantic shedding of skin. That’s how I ended up in Minnesota—fleeing a derailed career, a couple of DUIs, and relationships that had gone up in flames. Reinvention came first. Sobriety had to wait.

Even earlier, college had been a form of escape. I left behind the straight-A, tightly wound version of myself—the cautious, rule-following high school boy—and slipped into a new identity: hard-drinking, reckless, girl-chasing fraternity man. It worked, for a while. Until it didn’t. Until I had to run again.

But the first time I truly understood the power of escape, it hadn’t been a choice. It was ninth grade, and I’ll never stop believing it’s what kept me alive.

Years earlier, my father had moved us to a small, insular Mississippi town where I was immediately marked as an outsider. At first, that status was thrilling. As the new kid, I arrived unburdened by history. I was shiny, interesting. For the first time in my life, I was popular. People laughed at my jokes. Girls asked me to dance on Saturday nights at the youth center. Boys thought I was cool. I belonged—until I didn’t.

Because I wasn’t becoming the boy they wanted. I didn’t play sports. I liked books. I didn’t hunt, didn’t care about the Ole Miss Rebels, didn’t fit. The admiration curdled quickly. The laughter took on an edge. The names—sissy, freak—trailed me down the halls. Recess became a gauntlet of shoves and whispered slurs. Even teachers sometimes joined in. I was ridiculed in class with no one stepping in to stop it.

I learned that trusting others and letting your guard down was dangerous.

I hid the truth of my torment from my parents. My mother must have suspected—she promised that someday the smart kids would be the ones who mattered. That I just had to hold on. So I buried myself in schoolwork and prayers. I tried to disappear. But puberty had other plans. It made me more visible, not less.

Then came the thing I feared most: I began noticing boys in a way that terrified me. On a band trip, an older roommate touched me. I touched him back. It was like a door had blown open to a place I knew I wasn’t supposed to go. I wanted more. I was horrified. I slammed the door shut and tried to pretend it had never happened.

But pretending was getting harder. My younger brothers were about to join me in school. They’d see what I had become—mocked, powerless. They’d lose respect. My parents would learn the bruises and torn clothing weren’t from games. I would lose my last place of safety.

After four years, I had nothing left. I was tired. I didn’t want to disappear metaphorically. I wanted to stop existing altogether. I had an ulcer. My hair was falling out. I threw up every morning. I had once believed adulthood would be my freedom—that if I could just make it to eighteen, I could finally outrun all this. But I didn’t think I’d last that long.

Once you begin planning your death, even in a town that small, the options seem endless—bleach, train tracks, my father’s guns, my mother’s tranquilizers. I chose the pills. I wanted the exit to be quiet, even beautiful. I imagined a bath, the Ames Brothers crooning Sentimental Journey from the Magnavox. I wrote a note.

But before I could collect the pills, my father announced we were moving—back to Laurel, a bigger town where no one knew my shame. I didn’t say a word. I just knew: this was my second chance.

And this time, I would be careful.

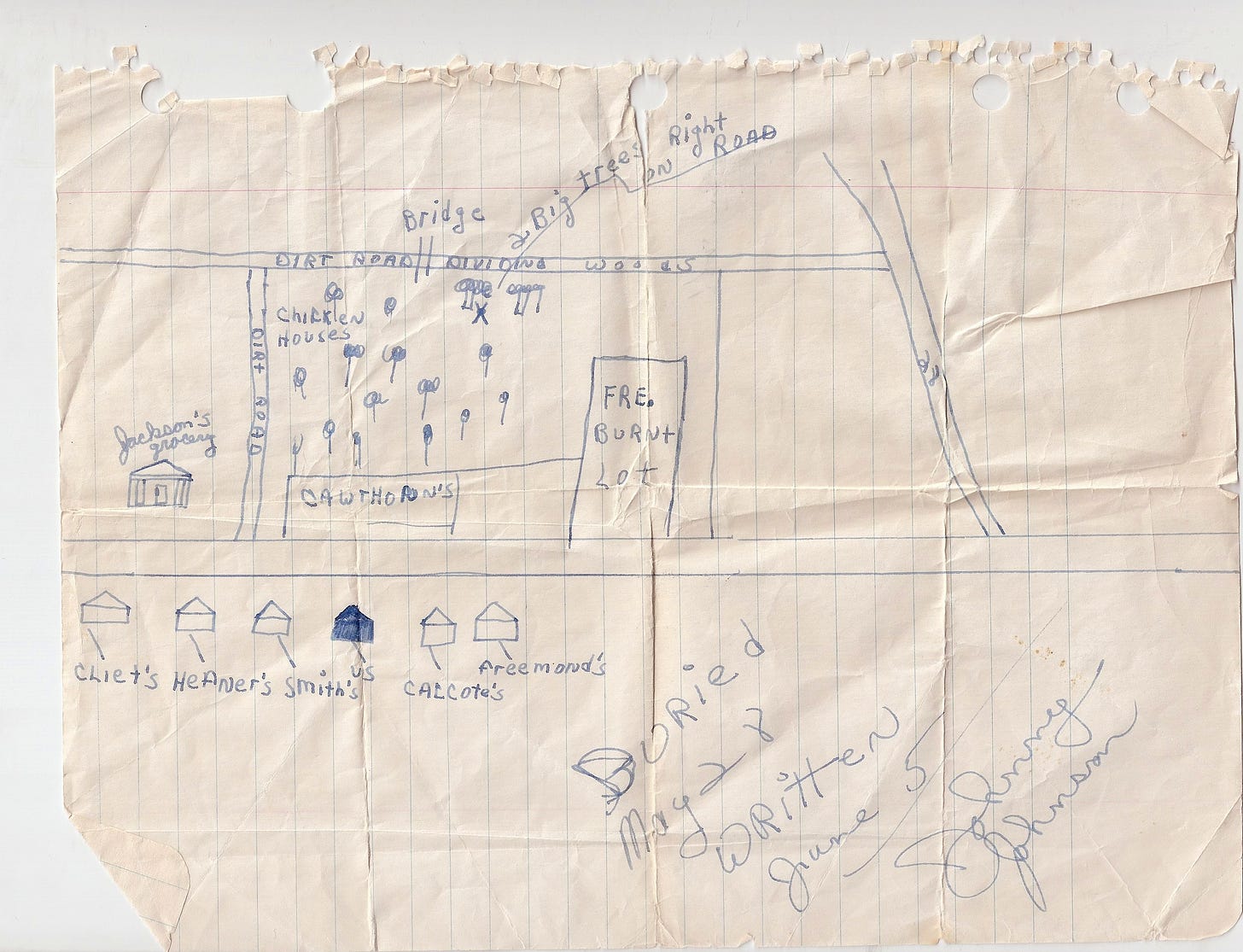

That summer, I held a private funeral for the boy I could no longer afford to be. I gathered a handful of relics—childhood keepsakes, a poem, a red diary with a tiny key, a drawing of my dog Pedro, a snippet of tape from my toy recorder whispering, When you find this, I hope you are happy. I buried them in a coffee can in the woods and took a photo of the spot with my mother’s Instamatic. I still have the map.

The rest of the burial was internal. I stifled my laughter. I stiffened my walk and voice. I avoided eye contact. I memorized facts. I recited rules. I killed spontaneity.

But the urge to write, to tell a story, never quite died. By my senior year, I felt the pressure to declare a future. In my mind, one’s career was a defining statement of manhood. I had loaded my schedule with science and math, the respectable tracks. But beneath the geometry and formulas beat the heart of a romantic.

I had become a closet poet, scribbling verses in secret. But in 1960s Mississippi, no boy—certainly no boy like me—was going to announce he’d just written a love sonnet. Still, college was coming. A new place. Maybe I could find a way to study literature without drawing too much attention.

But I still needed permission—from my father, who’d be paying the bills.

Men, I’d learned, valued competition. So I entered a poetry contest, hoping to win on merit and dress the thing up in masculine credentials. The prize: reading the poem aloud on Class Day. If I won, I’d show it to my father. If I lost, he’d never know I tried.

I was announced class poet. I told my father the whole senior class had voted for my poem, beating out dozens of others. I didn’t mention that only two girls and I had submitted.

He said he wanted to read it. I handed it over, hoping for a word of praise. Some sign of approval that this was something a man could do. Instead, he took out a pen and corrected my spelling and punctuation, then handed it back. That was the moment I decided I would be a businessman like him. It would be another quarter century before I would reinvent myself into a writer.

I read the poem on Class Day. People clapped. My mother beamed. The poem went into the family scrapbook, next to my brother’s newspaper clippings for breaking the state track record for the 440.

But it wasn’t enough. My father had seen something in me, and I could tell it repelled him—something that couldn’t be fixed with correct spelling.

There was one last hope: sex. I had no trouble becoming aroused around girls, thanks to my uncanny ability to confuse panic with desire. I spent my senior year locked in desperate make-out sessions, hoping sex would be my cure. That it would make everything right.

My last chance was Jamie—my prom date, a fellow trombone player, a kind, funny girl who had just been through a breakup. We danced to the Stones and Otis Redding. Later, in the car, we kissed. I pushed the moment forward. We drove to Mason Park, slipped into the shadows. We undressed.

We were ready. At last, I’d be in on the joke. The punchline to all those lewd stories in the school smoking area.

I looked at Jamie. Moonlight shimmered in her eyes—tears.

She pulled away, gently, like a sister might, and said, “Oh, Johnny, what will become of you? How will you ever survive out there?”

She was heartbroken—for me. I didn’t understand. Only that in that moment, I wasn’t her lover. I was something to be pitied.

I’d let my guard down with her. She knew me too well. I would have to be more careful.

So I recommitted. Shut up. Keep my head down. White-knuckle it until either God changed me—or got me out so I could reinvent myself again.

We dressed and I took her home.

Now, all these years later, I wonder about the parts of myself I left behind—the instincts I buried, the truths I was too afraid to claim. Do they disappear? Or do they wait, patient and whole, like artifacts buried in the ground, waiting to be unearthed?

Maybe the past isn’t something we escape. Maybe it’s a country inside us, waiting to be rediscovered.