The Hidden Weave of Race

When I first moved to Minnesota, what struck me was the whiteness of it all. I had never lived in a place where African Americans weren’t part of the visible, daily life. My first thought was: Where do they keep all their Black folks?

Eventually, I found the Northside—an economically isolated section of town where much of the Black population lived. I felt oddly grounded by its existence, perversely comforted to discover that even the “enlightened” North had its own version of a colored quarter. It confirmed what I had always been told growing up: Northerners were just as racist as we were in the South—maybe more so. They just dressed it up in better manners.

Minneapolis proved to be an easy place to be a racist. In this liberal haven of Humphrey, Mondale, and McCarthy, no one ever asked me to stop telling racist jokes, even in company meetings. People just laughed—or winced politely—and chalked me up as incorrigible, colorful. A real character.

I had never been called a “real character” before. I relished it. People in Minnesota were too full of “Minnesota Nice” to confront me. And, disturbingly, my worst behaviors seemed to make me more successful. They won me approval. They made me one of the guys.

Once again, I had reached for racism as a shield, for cover. This time, not to harm others outright, but to deflect attention from my queerness.

When the company owner promoted me to vice president of human resources in our all-white organization, he pulled me aside for some fatherly advice. I revered this man. He had created and marketed the world’s best-selling personal development program. He was a legend in the human potential movement.

His guidance was simple.

“You’re the gatekeeper now,” he said. “You decide who joins the family. Just make sure they’re people like us. People who won’t upset our rural field force.”

Then he winked.

He didn’t need to say more. The message was clear: Don’t hire minorities. Don’t hire anyone who might make people uncomfortable. He confirmed what I had already suspected about Minneapolis: their racism mirrored Mississippi’s. They just knew how to keep it out of the newspapers.

And so, in the height of the Affirmative Action era, I knowingly discriminated. I screened out Black candidates. I avoided hiring anyone who seemed gay—worried it might cast suspicion on me.

By age 37, I was five years sober and running my own company. I had learned to talk the talk around race. I performed the right gestures and kept the proper distance. I condemned the South’s vulgar racism, held it up as something I had evolved beyond. I had done my therapy, confronting family issues and my own sexual denial. I had tended to my psychic wounds and declared myself reborn.

That story worked until one spring evening in 1988. One wound had gone neglected and now demanded my attention.

PBS was airing archival clips in honor of the twentieth anniversary of Dr. King’s assassination. The footage was familiar—Black people marching down Main Streets in small Southern towns, soaked in sweat, wrapped in the heavy, humid heat of Mississippi. I could smell it. I could feel the sting of dust in my nose.

But this time, I saw something I had missed as a child: the white people. Not just in the background but in front and center. Lining the streets. Jeering. Throwing rocks. Waving Confederate flags.

My people.

Then I looked again at the marchers—King, Abernathy, Carmichael—and realized something I had never fully grasped: this wasn’t just Black history.

This was my history.

And I knew nothing about it.

These people—white and Black alike—and the space between them, had shaped me. And yet I had been raised in near-total ignorance of that shaping. The version of American history I was taught was not merely incomplete but fraudulent. A sin of omission.

Every day, I had been shaped by race. And yet I had never been given language for it. I had been told that whiteness was neutral. That my story stood on its own. But it didn’t. It stood on silence.

It felt as if a curtain had been pulled back from my soul.

I remembered the Black people from my childhood—men raking straw in our yards, women cleaning our homes, cooks in the cafés, porters, delivery men, Saturday shoppers. What I remembered most wasn’t what they said. It was that they didn’t say anything at all.

And neither did we.

We weren’t supposed to listen. Their thoughts didn’t matter. They had been made invisible by design. Even in our sermons and history books, their voices were absent.

Their enforced silence propped up my sense of self. Their erased dignity embellished my own.

I began to understand: much of what I believed about myself—about my country, my people, my identity—was a lie. And that lie had a cost—not just for those it erased but for me, too.

I realized I would never truly understand my own story unless I understood theirs. The story of Black Americans wasn’t adjacent to mine—it was fused to it. Our histories were interwoven, co-authored.

They had made me. And I had helped create them.

I’m not the first white American to come to this recognition—that our personal histories are stitched together from myths, convenience, and privilege. That we have all been traumatized by race, whether we know it or not.

I wanted to begin undoing that trauma. I needed to get out of my head and into theirs—not for their salvation, but for mine. Because within their silence lay a missing piece of my soul, of my humanity.

But where to begin?

The very next day, I read a feature in the Minneapolis Star Tribune: “Is the Dream Still Alive?” A collection of reflections on the legacy of Dr. King’s 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech.

One quote stopped me: Fannie Smith, the Black mayor of Falcon, Mississippi—a Delta town of 300 people. She was my age. Eloquent. Grounded. Unapologetic. I had found my entry point.

After a few calls, I tracked her down. Her “real” job was running the Snappy Sack Grocery. I reached her there.

“Mayor Smith,” I said, “you don’t know me. I’m a white man, raised in Mississippi—same time, same place, but in a very different world. I’ve come to believe that the story I was told about who I am was mostly fiction. I think your story may hold pieces of mine. Would you be willing to share it with me?”

She didn’t hesitate.

“Do I have stories?” she said. “You got a week?”

I laughed. “Will you share them?”

She replied, “If you want to hear them, you have to come down here and get them.”

I booked a flight to Memphis, rented a car, and drove to Falcon. The town was a scattering of crumbling houses and open ditches. I passed a peeling white cinderblock building with a police car on blocks out front. Someone had hand-painted City Hall over the door. It was locked.

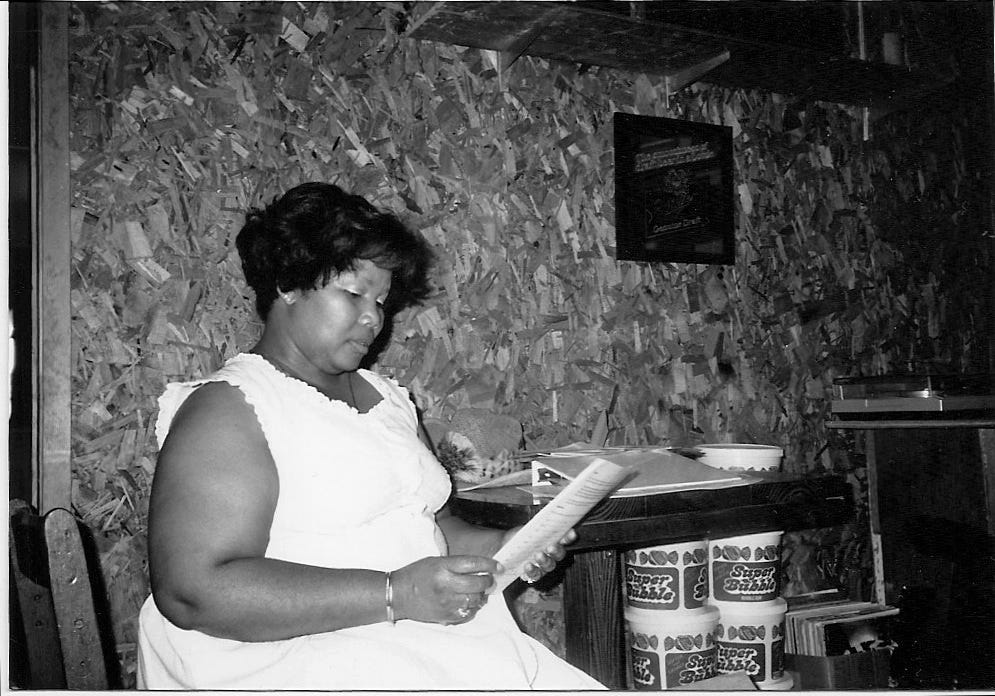

I found Mayor Smith at the Snappy Sack, behind the counter. She handed the register over to her brother and took me to the storeroom in the back. We talked for hours.

She was warm, sharp, and unflinchingly honest. When I asked how much had changed since King’s death, she smiled and said, “Well, I’m Black and mayor of this town. That wouldn’t have happened before the ’60s. Then again, there are 299 Black folks here and one white lady, who lives on the other side of the tracks. I don’t think she voted for me.”

Every Southerner, Black or white, has a story about the first time they learned color mattered. Mine was with Mr. Joe, the man I found raking our neighbor’s yard, whom I was told not to talk to because he was Black. Hers was with her grandfather—a respected man in the community—who was hit by a car while walking along the road.

She found him dead in the ditch the next morning.

When she and her mother reported it to the white sheriff, he refused to investigate.

“He’d lived a good life,” he said. “No need to stir up trouble.”

“Granddaddy could’ve been a dog,” she told me. “That’s when I learned about color.”

In my mind, her grandfather became another face of Joe—the part of him I had never been allowed to see. A church deacon. A grandfather. A wise man. A Mister.

But in our world, he was just a yard boy.

Mayor Smith didn’t stop with her own story. She took me to meet aging civil rights workers who had marched with King in ’66, 80-year-old midwives who rode muleback to deliver babies no white doctor would touch, and sharecroppers who had risked their lives to register to vote.

She revealed a hidden history—full of dignity, defiance, and unacknowledged heroism. As one elderly man put it, “When God handed out possessions, He must’ve given the white man the pencil and the Black man the hoe. That’s why we ain’t in your history books.'“

These men and women taught me that the movement had been led by the everyday— maids, mothers, and “Saturday night brawlers.” Women who stood up not only to the Klan but also to the Black clergy and teachers who were beholden to white power and paralyzed by fear. These people may have been victimized, but they were not victims. Nor did they want to be treated that way.

After meeting Mayor Smith, I made dozens of return trips to Mississippi. I talked to African Americans who shared their stories with startling generosity—funny, tragic, intimate stories. I think they trusted me not because I came to save them, or confess to them, or memorialize them. But because they sensed I was broken too. They held pieces of my history.

And they were Christians. They said they were called to help where they could.

In return, they asked for one thing: the truth.

What’s it like to be a racist? How does someone become that way? Why would anyone want to change when being on top feels so good?

They didn’t want to hear how I had conquered racism. They wanted to hear how I still wrestled with it.

I was surprised that my answers didn’t anger them. If anything, they seemed grateful. I began to see that this is the piece of the story we white folks hide from them—the ugly truth of our own souls.

And so began my journey to re-remember my life.

To stitch back together a story that includes the voices, the labor, and the sacrifices of those long silenced. To acknowledge that my sense of superiority was not only unearned, but subsidized by their invisibility.

Joe. Mayor Smith. Her grandfather. The field hands. The midwives.

They did not just witness my story. They authored it.

And their forced silence did not just impoverish them—it disfigured me.

Share this post