Writing a memoir has taught me that, when delving into family stories, I need to ask two crucial questions: What does this story reveal about my family? And even more importantly, what does it conceal? Many of the narratives pa

ssed down through generations are carefully crafted to mask underlying truths, truths that even the memoirist may be reluctant to uncover. Sometimes, we simply can’t see these hidden realities because we’re still in the picture, playing our assigned roles.

One approach I’ve found helpful in stepping outside my cultural, historical and family narratives has been to invite friends to visit my Mississippi home with the expressed purpose of observing and describing my world through their eyes. It’s startling to hear what they notice that I’ve been conditioned to overlook—those things I was raised not to see.

I stumbled on this method of “assisted revelation” years ago when Tim, a friend from Minneapolis, joined me in Mississippi for a stay with my parents. As we sat on the porch chatting, my mother insisted on showing us photos from their 40th wedding anniversary. It had been a sizeable event, and as I flipped through pictures of aunts, uncles, brothers, and their families, a growing sense of unease crept over me. My absence from the photos weighed heavily.

“It looks like y’all had a great time,” I remarked, trying to keep my tone light.

My mother, with a pained look, responded, “Yes. I was hurt you didn’t come.”

The feeling that I had let her down clung to me for the rest of the afternoon. I felt like a “bad” son.

Later, Tim pulled me aside and asked how I was holding up. I confessed to him how guilty I felt for not attending the party, how I should have been there for my parents. He looked at me in disbelief and said, “But you weren’t invited! No one told you about it.”

I was so entrenched in my family’s dynamic that the thought that it wasn’t my fault hadn’t even crossed my mind. It didn’t fit the story I had internalized. Instead of feeling appropriately angry that I was excluded—anger was never an option in my family—it was easier, more acceptable, to feel the familiar guilt of not being the dutiful son; to feel the need to take care of my mother instead of myself. What was obvious to Tim had completely escaped me.

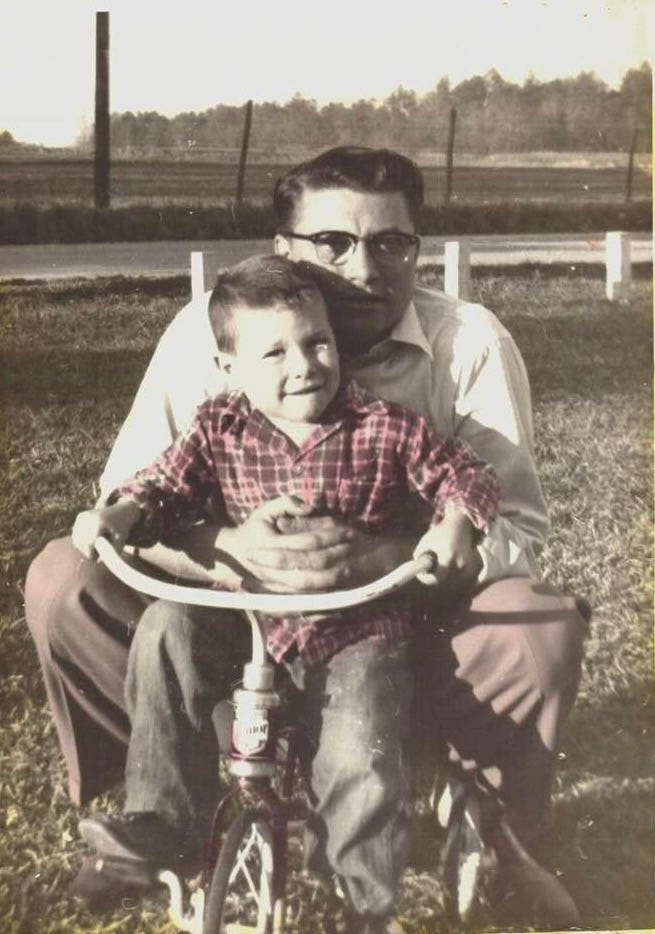

Later that evening, I pulled out all our old family photos and shared them with Tim. I narrated the story of how close my mother and I were during my youth, and how absent my father had been. But after looking through dozens of pictures of my parents with me as a child, Tim pointed out something I had never noticed:

“You know, your mother isn’t touching you in any of these pictures. Look how far off she stands. It’s your dad who holds you. It’s him you’re showing affection to, not your mother.”

That couldn’t be! I looked through the photos again. He was right! The realization sent me reeling. The story in my head had always been that my dad was distant and to blame for our family’s distress. It was my mother who was the loving, nurturing one—the one who tried to get my dad and me to talk to each other, the glue that held us together.

But when Tim pointed out what he saw, memories began to resurface. My dad and I had indeed been close once, before I started school. He had been my buddy, especially after my twin brothers were born and my mother became overwhelmed. But somewhere along the way, that closeness had faded, and he became the enemy. I then remembered how my mother would come into my room late at night before I fell off to sleep and ask, “Who do you love most, me or your father?” I knew the answer she demanded.

I felt a sudden rush of emotion for my father, remembering the affection he had shown me as a child, how tender he had been, and the resistance I had built up against the demonstration of his love. The ice inside me splintered. Overcome, I sobbed, grieving that loss. I went into the den and told my dad I loved him, and how I had missed him. He cried as well. As we moved to embrace each other, my mother, who had been watching with visible alarm, quickly joined us, literally pushing us apart and inserting herself between my father and me and saying, “I’m so happy for you both. I’ve always wanted this.”

In that moment, so much became clear. My mother had a personal stake in me seeing my father as distant, unapproachable, and unloving. She was the one who loved me the most, who interceded between me and an angry dad who oppressed us both. It was a narrative she had carefully maintained, one that I had unconsciously accepted until that moment.

Since that day, I’ve invited other friends to Mississippi who might point out additional blind spots. For instance, I’ve returned with Black friends who opened my eyes to racism that was everywhere except in my consciousness. My husband Jim, a Minnesotan, often travels with me and points out distinctions of culture and the contours of nature that I grew up with but took for granted. These observations have enlarged my world and changed how I see myself in it. They have given depth to my writing.

It’s an unsettling experience when we stumble upon a false narrative, a cherished story that gives our life order regardless how distorted: the picture-perfect family, “the greatest country on earth,” the demonization of the other, the myth of invulnerable masculinity or compliant femininity, the superiority of a people, the infallibility of a parent, a leader, a religion. They all await our readiness to allow that one piece of contradictory evidence to shatter the entire picture and free us to live out a more authentic truth.