I was born on May 9, 1951. There is no reason you should know that date, except that while my mother was giving birth to me in the Masonite Hospital, Willie McGee, a Black man, was being legally lynched only four blocks away at the courthouse to the cheers of over a thousand white citizens. If you walked a bit north, you couldn’t miss the mansion a young Leontyne Price regularly helped her aunt clean until the white lady of the house heard her sing and got her into Juilliard. Ms. Price went on to become the legendary soprano at the Metropolitan Opera. And if you kept on walking a few blocks to the other side of town, you might spy a respected businessman and Sunday school teacher, Sam Bowers, the owner of Sambo’s Amusement Company, closing up shop. He was only a few years away from becoming the Imperial Wizard of the KKK of Mississippi Burning fame and charged with planning and executing some of the bloodiest atrocities of the Civil Rights Era.

Home sweet home.

The insanity is not that these world-shaking events happened in the same small town in Mississippi where I grew up. No, the insanity is that I would be a grown man before learning about them. Like most white citizens, I was isolated from these events and assumed they had nothing to do with me.

It shames me to admit that in the white-defined society in which I was raised, we considered Black individuals merely background. It was worse than physical segregation. This was psychological segregation. It wasn’t so much that we were taught not to associate with Black people; close association was unavoidable. Instead, we were taught not to see half the population as people, only as functionaries—maids, yardmen, the colored help.

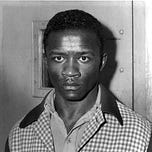

For instance, I’m sure I would have never heard of Willie McGee without coming across his name while researching my novel. Sitting in the Laurel Community Library, on a lark, I decided to check the newspaper archives to see what happened the day I was born. “Willie McGee Pays with Life!” the headline screamed. The breathless reporter described how they set up Mississippi’s one-of-a-kind traveling electric chair in the same courtroom where McGee had been found guilty, facing the jury box. The paper reported that Albert Einstein had publicly condemned the execution. There were protests in New York and Paris. Jean-Paul Sartre called the whole thing barbaric. That didn’t deter a thousand white people from standing on the Jones County Courthouse lawn, enthusiastically waiting for “justice” to be done.

The rites of execution were well-documented. A local radio station broadcast it live. In papers worldwide, there were photos of the handsome 37-year-old being led into the courthouse; of the crowd standing by, waiting for massive generators sitting out on the flatbed trucks, humming steadily, finally to surge and for the streetlights to dim, signaling the end of life. There was an odd photo of schoolboys in the upper limbs of a magnolia tree, peering down into the second-story courtroom, watching from their perch the actual electrocution. Then, a photo of a shrouded body on the gurney exiting the courthouse to another round of cheers.

Yet I would not hear a word about this international cause célèbre that unfolded on my very doorstep until nearly a half-century later. After I read the account, I questioned my parents, friends, and those who were my teachers. None had the vaguest memory of Willie McGee. Black people, on the other hand, remembered it well. They remembered that as children, they were marched from school to the funeral parlor and forced to look into the casket at McGee’s body to impress upon them what happens when Black men overstep their bounds.

Since then, I have learned that this social amnesia among whites is not so uncommon. Dozens of white Southerners have confessed to me they have been astonished to learn of the things that went on in their backyards. We were taught not to see these things or the people to whom they happened. Somehow, they were effectively placed outside our cultural field of vision. We missed the marchers and the Freedom Riders and the lunch counter protests and the voting rights rallies and the eloquence of Martin Luther King prophesying in a church on the other side of town or remember that very church being bombed. It might as well have been the other side of the world.

How could this be? I found a clue.

The day after the execution, the mayor of Laurel wrote an open letter to the citizens, suggesting that we put this unpleasantness behind us and move on. I believe he was asking that we do something we were already good at doing.

I’ve come to believe that the guardian of injustice is willful cultural blindness

And we resented anyone who tried to make us see. That is why Leontyne Price, after she became world-renowned, singing before the crowned heads of Europe, still had to use the servant’s entrance when she visited her white benefactor at her home in Laurel. Her furs and jewels and limousine made no difference. As the lady of the house was quoted in Time Magazine, she just didn’t want to upset anybody.